Pompey’s Curia is known as the site where Julius Caesar was stabbed to death on the ides of March in 44 BCE. It is of great importance to tourists, historians and archaeologists. After analyzing mortar samples collected from the Curia, researchers from Italy and Spain confirmed a previous hypothesis that the structure was built in three distinct phases, according to a recent paper published in the journal Archaeometry.

In ancient Rome, a curia was a structure where members of the senate met. The great Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey) built this special curia as a memorial to his own military achievements. A large theater section contained a temple, stage, and seating at one end; a large portico (with the general’s art and books) surrounded a garden in the center; and the Curia of Pompey was on the other side.

During the reign of Julius Caesar, Roman senators temporarily gathered at Pompey’s Curia after their usual Curia burned down at the Comitium in 52 BCE. (Followers of a murdered tribute named Publius Clodius Pulcher set it on fire while cremating his body.) Caesar’s planned replacement (Curia Julia) was under construction as a replacement meeting place when the ruler met his own brutal demise at the foot of the Curia from Pompey. The senators who killed him thought that murder was the only way to preserve the republic, but the assassination ultimately led to the collapse of the republic.

Leemage/Corbis/Getty Images

Although the theater complex would last for centuries, Pompey’s Curia did not remain open. After the assassination, the Curia was bricked up (and possibly set on fire) just 11 years after it opened. Later a latrine was built on the site. The curia was buried under more recent construction as Rome expanded and was not excavated until the 1930s as part of the destruction of parts of modern Rome by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to unearth ancient historical sites. In addition to Pompey’s Curia, those efforts revealed four temples. The remains of the structure are still visible in an area of Rome called Largo di Torre Argentina.

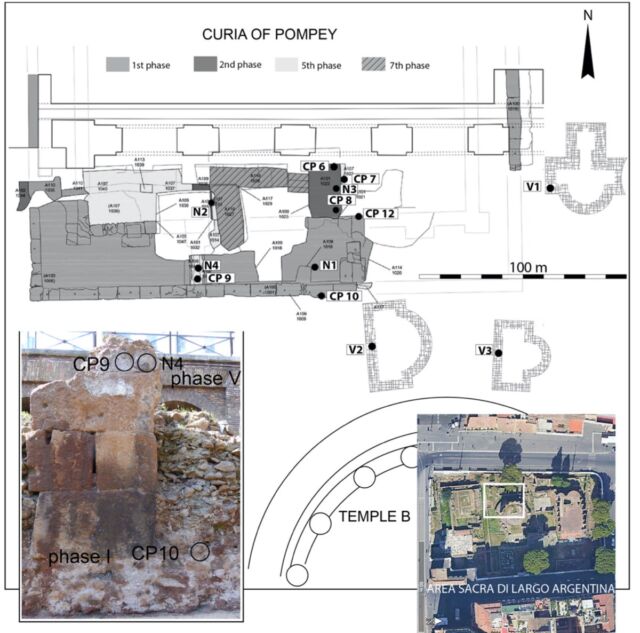

The suggestion that the curia was built in phases is not new. An earlier archaeological study analyzed the rock layers (strata) at the site and found that construction of the Curia began around 55 BC. pozzolan red (pink pozzolana) recovered from volcanic deposits near the city center. Around 19 BCE, during the reign of Augustus Caesar, there was a second phase of construction using pozzolan red extracted from a location further away. The third and final phase of construction took place during the Middle Ages.

Fabrizio Marra of the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology in Rome and his fellow co-authors sought additional confirmation of this hypothesis from the perspective of archaeometry. Specifically, they wanted to perform a chemical analysis of the mortar (concrete) used to build the curia to determine which quarries supplied the building materials for each construction phase. The team also analyzed samples from three basins at the site: two on the west side of Largo di Torre Argentina and the third on the north side of Pompey’s Curia.

A. Monterroso, JI Murillo, R. Martín and MA Utrero

As we have previously reported, ancient Roman concrete was in fact a mixture of a semi-liquid mortar and aggregate. Portland cement (a basic ingredient of modern concrete) is usually made by heating limestone and clay (as well as sandstone, ash, chalk and iron) in a kiln. The resulting clinker is then ground into a fine powder, with just a touch of plaster added – the better to get a smooth, flat surface. But the aggregate used to make Roman concrete consisted of fist-sized pieces of stone or bricks.

In his treatise the architecture (circa 30 CE), the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote of building concrete walls for funerary structures that could stand for a long time without falling into ruins. He recommended that the walls be at least 0.6 m thick and be made of “square red stone or of brick or lava laid in lanes.” The brick or volcanic rock aggregate should be bonded with mortar composed of hydrated lime and porous fragments of glass and crystals from volcanic eruptions (known as volcanic tephra).

“A large number of papers over the past 15 years have shown the exceptional care with which Roman contractors produced mortar and concrete,” Marra et al† wrote. Scientists have analyzed the mortar used in the concrete that makes up Trajan’s markets, built between 100 and 110 CE (probably the world’s oldest shopping mall). In 2017, the same team analyzed the concrete of the ruins of seawalls along Italy’s Mediterranean coast, which have stood for two millennia despite the harsh marine environment. The researchers discovered that the secret to that longevity was a special recipe using a combination of rare crystals and a porous mineral.

And last year, scientists analyzed samples of the ancient concrete used to build a 2,000-year-old mausoleum along the Appian Way known as the tomb of Caecilia Metella, a noblewoman who lived in the first century AD. The scientists found that the mortar of the tomb was similar to that used in the walls of Trajan’s Markets: volcanic tephra from the pozzolan red pyroclastic flow, which binds large chunks of brick and lava aggregate together. However, the tephra used in the tomb’s mortar contained much more potassium-rich leucite.