The Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering has developed a communication platform for people with complete locked-in syndrome.

A 36-year-old German man in a fully confined state was equipped with a new brain-computer interface (BCI) system that relies on auditory feedback. The man learned to adjust his brain activity in response to that auditory feedback to compose simple messages. According to a recent article published in Nature Communications, he used this ability to ask for a beer, for his caretakers to play his favorite rock band, and to communicate with his young son.

BCIs work with brain cells, recording the electrical activity of neurons and converting those signals into action. Such systems generally include electrode sensors to record neuronal activity, a chipset to transmit the signals, and computer algorithms to translate the signals. BCIs can be external, similar to medical EEGs, in that the electrodes are placed on the scalp or forehead with a wearable cap, or they can be implanted directly into the brain. The first method is less invasive, but may be less accurate because more noise interferes with the signals; the latter requires brain surgery, which can be risky. But for many paralyzed or incarcerated patients, it’s an acceptable risk.

Last year we witnessed two major milestones on the BCI front. In March 2021, we reported on Neuralink’s demonstration of a playing monkey pong using a brain implant wirelessly connected to the game’s computer. To achieve this, the company has successfully miniaturized the device and allowed it to communicate wirelessly. In April 2021, researchers from the BrainGate Consortium successfully demonstrated a high-bandwidth wireless BCI in two tetraplegic subjects.

This latest study used a wired implanted BCI. People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), popularly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, often become paralyzed and unable to communicate, although they are cognitively functional. Several tools have been developed to restore the ability to communicate, including BCIs that rely on eye movement. But patients in a fully confined state have lost even that little bit of motor control. This study documents the first successful demonstration of BCI-assisted communication in a fully confined patient.

The German man in the study was diagnosed with progressive muscle atrophy in August 2015, an ALS variant that selectively affects motor neurons. Within a few months, he was unable to walk or communicate verbally, and in July 2016 he was artificially ventilated and fed by a tube. The man initially communicated through an eye movement device, but his condition deteriorated.

Wyss Center for Bio- and Neuroengineering

Realizing it was only a matter of time before he completely lost control of his eye movements, the man’s family asked co-authors Niels Birbaumer of the University of Tübingen and Ujwal Chaudhary of ALS Voice gGmbH in Germany about alternative options. Initially, the man started using an external BCI system that allowed limited “yes” or “no” answers, which the man could use to select letters to form words and sentences. But Birbaumer and Chaudhary knew that even this soon wouldn’t suffice once the man became fully locked up.

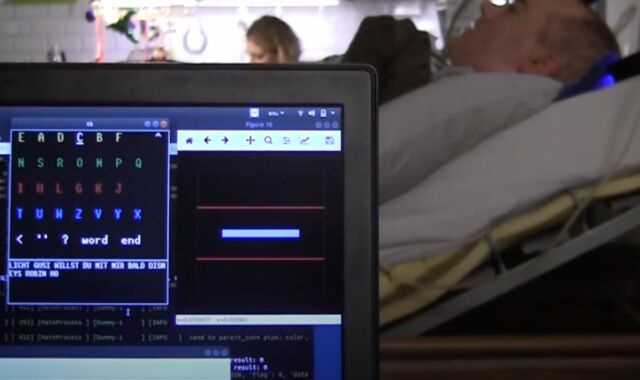

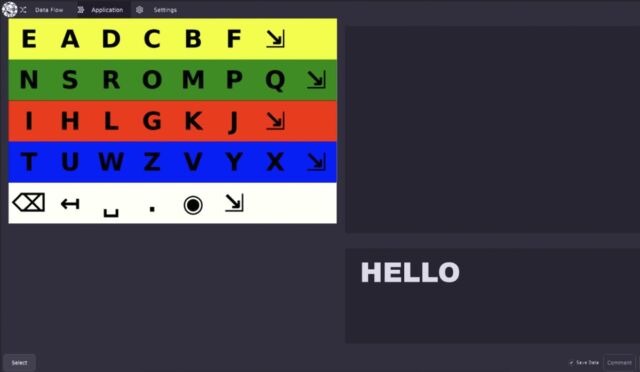

An implanted BCI was considered the best option and neurosurgeons in Munich performed the surgery in March 2019. They placed two microelectrode arrays in the patient’s left motor cortex (the dominant side) to detect neural signals, which are transmitted through a wired connection to a computer for processing. NeuroKey software would then decode and play that data as auditory feedback tones. The patient quickly learned how to modulate the sound tone and eventually modulate his neural firing rate to match the frequency of the feedback. After many months of training sessions, the man was able to select letters and spell words to communicate.

The first message was a simple thank you to Birbaumer and the rest of the team. Other reports related to the man’s care preferences: asking for a head massage or more gel on his eye (which was prone to dryness), and for a higher head position when there were visitors. He even made suggestions to improve the spelling system’s performance.

Wyss Center for Bio- and Neuroengineering

Finally, he was able to accommodate specific dietary requirements for his feeding tube: soup with meat, pea soup and curry with potato. And he asked for a beer and for his caretakers to play his favorite band, Tool, really loud. But it is the communication with his young son that is close to his heart, despite the article’s aloof academic tone:

ich liebe meinen cool (son’s name) – ‘I love my cool son’ on day 251; ‘(son’s name) willst du mit mir kale disneys robin hood anschauen‘- ‘Would you like to watch Disney’s Robin Hood with me’ on day 253; †everything von den dino ryders und brax autobahnund alle aufziehautos‘ – ‘everything from dino drivers and brax and cars’ on day 309; ‘(son’s name) moochtest du mit mir disneys die hexe und der zauberer anschauen auf amazon‘ – ‘Would you like to watch Disney’s witch and wizard with me on amazon’ on day 461; †mein groesster wunsch ist eine neue bett und das ich morgen mitkommen darf zum grillen‘ – ‘My greatest wish is a new bed and that I will have a barbecue with you tomorrow’ on Day 462.

The authors acknowledge that communication speeds for their system were much lower than measured in other studies involving ALS patients who were not fully confined, and they will continue to refine and improve their system. I doubt this German man and his family too much, as Birbaumer, Chaudhary and their co-authors gave them the priceless gift of reconnection.

DOI: Nature Communications, 2022. 10.1038/s41467-022-28859-8 (About DOIs).

List image by Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering