Infection by SARS-CoV-2 causes a dizzying array of symptoms beyond the respiratory distress that is its most notable feature. These range from intestinal complaints to blood clots to the loss of smell, and the symptoms vary greatly from person to person.

It will probably take years to figure out exactly what the virus does in the human body. But we got a little bit of data this week from a detailed study of images of the brains of COVID patients. The images were taken before and after the patients were infected. The results suggest that some areas of the brain associated with the olfactory system may shrink slightly after infection, although the effect is minor and consequences are unclear.

Hitting the biobank

This is yet another study that relies on the British Biobank. The Biobank enables users of the UK’s National Health Service to voluntarily match their medical records to their genetic profiles and provide medical researchers with a source of large population-level risk studies. In this case, a research team based largely in the UK combed the Biobank for people who had had brain scans before SARS-CoV-2 infection.

There are plenty of reasons to focus on the brain and COVID. Loss of smell is the most obvious. While we don’t currently understand the biological reason for this, SARS-CoV-2 clearly infects the nasal passages, which are where the nerve cells that sense odor molecules are. From there, just one nerve bundle connects to parts of the brain that process the signals we perceive as our sense of smell. This nerve bundle may be able to transmit the virus directly to the brain.

In addition to this direct connection, an infection can alter the brain indirectly. These include causing an inflammatory response in the brain or damage due to the blood clotting seen in some patients. But there are reasons to believe something is up, as there have been reports of an ill-defined “brain fog” that some people experience as part of long-term COVID. A number of small studies have also described damage to specific parts of the brain after infection.

So, to get a clearer picture of the brain, the researchers had more than 400 people who had had a brain scan prior to a SARS-CoV-2 infection get another scan afterward. And the researchers matched those patients with several hundred people who had not tested positive for the virus to also get brain scans and serve as controls.

shrink

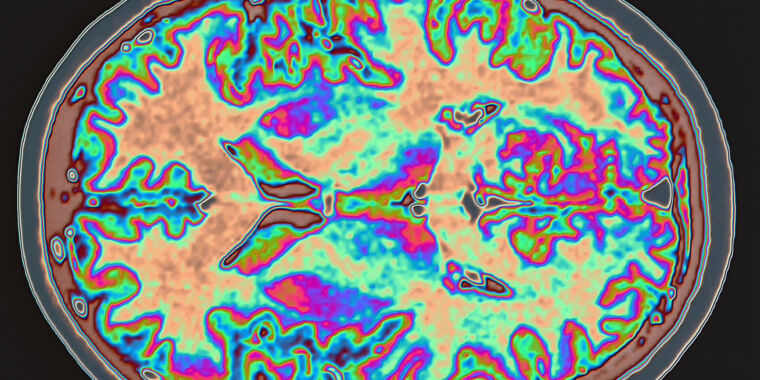

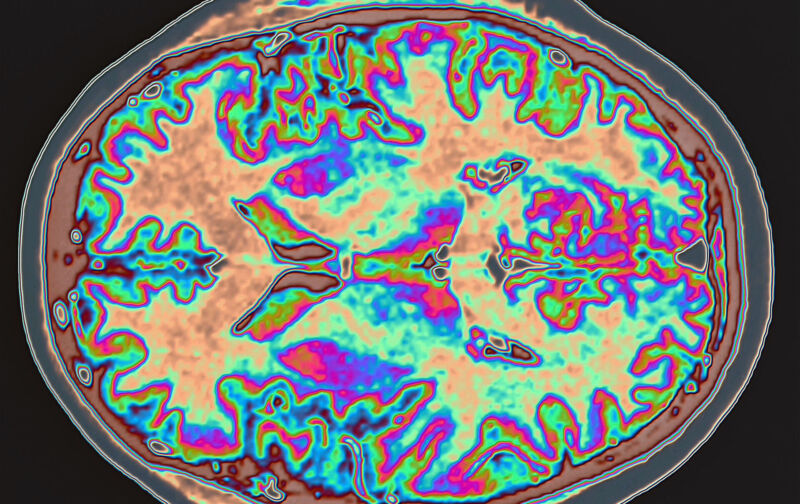

Using a software package that can compare two brain images, the researchers looked for changes in specific structures. They performed two separate analyses. One was based on hypotheses, in that it was limited to all structures known to be one or two connections away from the olfactory nerves in the nose. The second was an open search for brain structures that showed a difference between the before and after scans.

The software did find statistically significant differences between the two time points in infected patients, but the differences were generally small. Several regions of the brain shrank, usually by something on the order of 0.2 to 2.0 percent — a difference that would normally last about five years due to the natural decline that occurs with aging. The difference appeared to be due to changes in the brain’s “grey matter” — the bodies of the nerve cells themselves, rather than the white matter used to make connections between cells.

Most of these changes were seen in more than half of the infected individuals. So this is not the case where only a few people experienced large-scale changes that threw the numbers away. Similar results were seen when the 15 patients requiring hospitalization were removed and the data re-analyzed. That means the changes don’t seem to require a serious case of COVID-19.

About half of the areas identified in the general analysis were also identified in the hypothesis drive analysis, suggesting a fairly strong correlation between these changes and an association with the olfactory system.