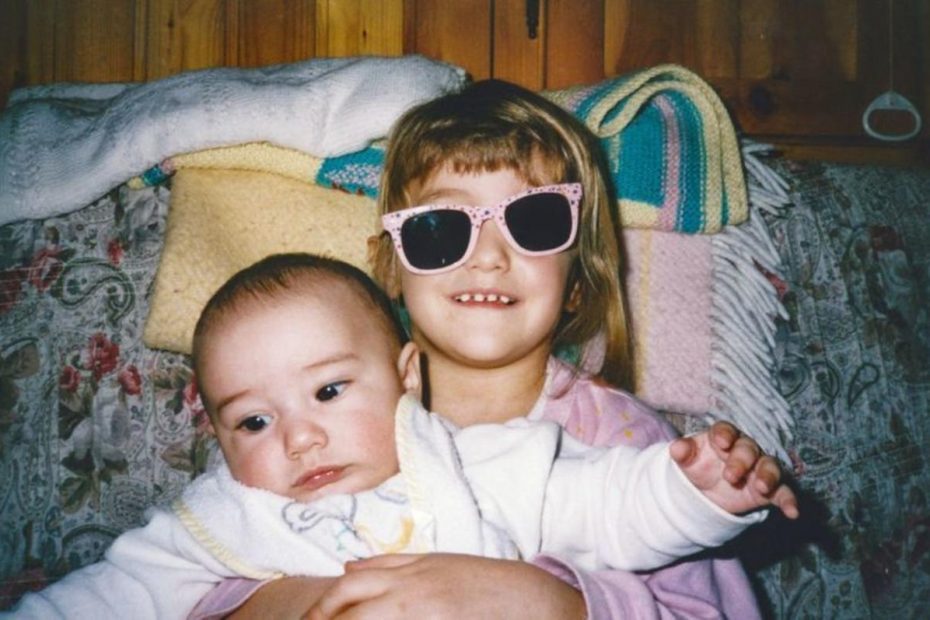

Growing up as the eldest sibling, author YL Wolfe often felt as if the boundaries between her role and that of her mother were blurred.

“By the time my youngest brother was born, when I was almost eleven, I was overwhelmed with feelings of responsibility for his well-being. I would always sit by his crib and watch him sleep, just to make sure he was safe,” Wolfe, the oldest of four, told HuffPost.

'It wasn't that I didn't think my mother was competent, but rather that I felt like we were both At that point in my life, I was responsible for the family,” she explained. “Like I was literally an 'other mother', instead of a big sister.”

In other words, Wolfe is very familiar with the “eldest daughter syndrome.” The Internet is full of thoughts about the fate of the eldest daughters and tweets about how we – I might as well reveal my prejudices here – should unite in a union: “If you are the eldest sibling and also a girl, you may be entitled to financial compensation,” a woman joked on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter.

Although “eldest daughter syndrome” is a pop psychology term—you won't see it as an official diagnosis in the DSM-V—a new study suggests there may be more science behind the pseudo-syndrome than previously thought.

A University of California, Los Angeles-led research team found that in certain cases, firstborn daughters tend to mature earlier, allowing them to help their mothers raise younger siblings.

Specifically, the researchers found a link between early signs of adrenal puberty in firstborn daughters and their mothers who had experienced high levels of prenatal stress.

Why does the age of adrenal puberty matter? Changes in the skin (for example, acne) and body hair occur during this phase, but so do changes in brain development. The processes of adrenal puberty are thought to promote social and cognitive changes; In short, superficial physical changes correlate with emotional maturity.

When times are tough and mothers are stressed during pregnancy, it is in the mother's adaptive interest for her daughter to mature socially more quickly, says Jennifer Hahn-Holbrook, one of the study's co-authors and an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Merced.

“It rather gives mother a 'helper-at-the-nest', helping the females keep the last offspring alive in difficult circumstances,” she said.

Layland Masuda via Getty Images

Notably, adrenal puberty does not include breast development or the onset of menstruation in girls (or testicular enlargement, in the case of boys). The study states that girls become mentally mature enough to care for their younger siblings while physically being unable to have their own children, which would naturally distract them from the responsibilities of their older daughters.

Older brothers are apparently out of sorts when it comes to this kind of parentification: The researchers didn't find the same result in boys or daughters who weren't firstborn.

“One reason we did not find this effect in firstborn children who are sons could be that male children are less likely to help with direct childcare than female children, leaving mothers with fewer adaptive incentives to accelerate their adolescent social development. Hahn-Holbrook explained.

Additionally, she said, previous research suggests that the timing of puberty in women is more modifiable in response to early life experiences than in men.

The results of this study, published in the February issue of Psychoneuroendocrinology (say, five times fast—or just once), were a long time coming: Researchers followed the families for 15 years, from pregnancy through the babies' teenage years. .

Researchers recruited women from two obstetric clinics in Southern California during routine prenatal care visits in the first trimester. On average, the women were 30 years old and pregnant with one child, not twins.

For about half of the participants it was their first pregnancy. The women did not smoke or use steroid medications, tobacco, alcohol or other recreational drugs during pregnancy. They were all over 18 years old.

The women's stress, depression and anxiety levels were measured at five different stages of pregnancy, and then measured cumulatively. The depression assessment asked the women to rate the truth of statements such as “I felt lonely,” while the anxiety question asked how often they felt certain symptoms, such as “nervous.”

Of the children born to these mothers, 48% were female and 52% male.

As the children got older, markers of adrenal and gonadal puberty were measured separately – things like body hair, skin changes, height growth or growth spurts, breast development and the onset of menstruation in women, and voice changes and facial hair growth in men.

The study also measured childhood adversity to account for other factors known to be associated with early maturation or signs of puberty in children, such as the death of a parent or divorce before age 5 and the absence of a father and economic insecurities between the ages of 7 and 9.

Taking all that into account, it was the oldest girls who matured fastest when their mothers experienced high levels of prenatal stress.

Other studies suggest that highly responsible eldest girls can reap some rewards later in life: a 2014 study found that eldest daughters are the most likely to succeed regardless of sibling type, while a 2012 study found that those who those born eldest are more likely to hold leadership roles.

The older sister kisses the younger one as she sits in a hammock. Afro sisters. Curly hair.

Renata Angerami via Getty Images

The findings ring true for Wolfe, the aforementioned author who said she felt like a second mother to her siblings while growing up.

“I'm not at all surprised by what the study found,” Wolfe said. “My story is slightly different: I went through real puberty at age 12, not just adrenal puberty, although I suspect I went through early cognitive maturation.”

The study is also interesting for another reason: The findings add to social scientists' growing understanding of fetal programming, a fascinating area of research that examines how stress and other emotional and environmental factors women experience during pregnancy affect their affect children long after birth.

“This is a unique find and fascinating to look at through an evolutionary lens,” Molly Fox, an anthropologist at UCLA and one of the study's co-authors, said in a press release.

In an interview with HuffPost, Fox elaborated on how fetal programming works.

“A fascinating theory is that while you are still a fetus in your mother's womb, you receive cues about what the world will be like, and that your body can flexibly adjust the shape of your life cycle to best suit the circumstances you expect to encounter,” she said.

Fox and her co-authors are happy to have their work available to the public to read, especially after following the families for so long. The fact that the findings were published just as a cultural conversation about eldest daughters was breaking out was just icing on the cake, especially for Fox, an eldest daughter. (She's a twin.)

“As a co-parent, I think it is a special role in any family because of the opportunity for a close bond with my mother and the ability to care for my younger siblings,” she said.

Spoken like a true eldest daughter. This article originally appeared on HuffPost.