Aurich Lawson / Getty Images

Curiosity drives all science, which may explain why so many scientists occasionally find themselves in a particularly eccentric line of research. Have you heard about the World War II-era plan to train pigeons as missile guidance systems? How about experiments on the swimming ability of a dead rainbow trout or that time biologists tried to scare cows by popping paper bags near their heads? These and other unusual research efforts were honored tonight in a virtual ceremony to announce the recipients of the 2024 annual Ig Nobel Prizes. Yes, it’s that time of year again, when the serious and the silly collide—for science.

Founded in 1991, the Ig Nobels are a good-natured parody of the Nobel Prizes; they honor “achievements that first make people laugh and then make them think.” The unashamedly campy awards ceremony features miniature operas, scientific demonstrations and the 24/7 lectures in which experts must explain their work twice: once in 24 seconds and the second time in just seven words. Acceptance speeches are limited to 60 seconds. And as the motto implies, the research being honored may seem ridiculous at first glance, but that doesn't mean it's without scientific value.

Viewers can tune in to the usual 24/7 lectures, as well as the premiere of a “non-opera” featuring several songs about water, in keeping with the theme of the evening. In the weeks following the ceremony, the winners will also give free public lectures, which will be posted on the Improbable Research website.

Without further ado, here are the winners of the 2023 Ig Nobel Prizes.

Peace

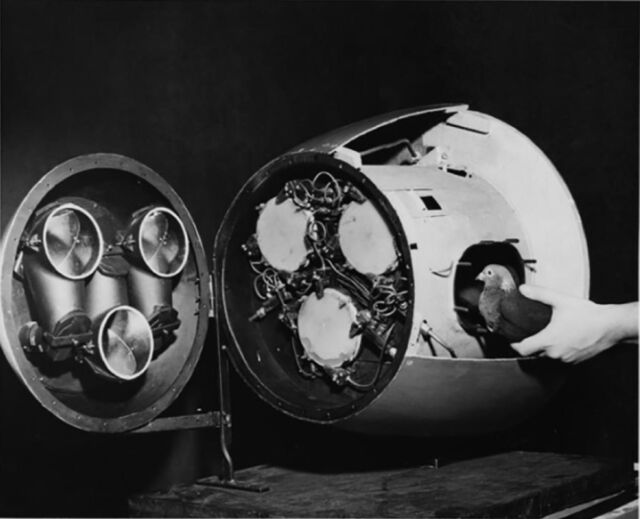

Credit: BF Skinner, for experiments to investigate the feasibility of housing live pigeons in rockets to determine the flight paths of the rockets.

This entertaining 1960 article by American psychologist B.F. Skinner is a kind of personal memoir that “tells the story of a crazy idea, born on the wrong side of the tracks intellectually speaking, but ultimately vindicated in a kind of middle-class respectability.” Project Pigeon was a World War II research program at the Naval Research Laboratory aimed at training pigeons to serve as missile guidance systems. At the time, in the early 1940s, the machinery needed to guide Pelican missiles was so bulky that there wasn't much room left for actual explosives—hence the name, because it resembled a pelican “whose beak can hold more than its belly can.”

Skinner reasoned that pigeons would be a cheaper, more compact solution, since the birds were particularly good at responding to patterns. (He dismissed the ethical questions as a “peacetime luxury,” given the high global stakes of World War II.) His lab devised a novel harness system for the birds, positioned them vertically above a transparent plastic sheet (screen), and trained them to “peck” at a projected image of a target somewhere along the New Jersey shore on the screen—a camera obscura effect. “The guidance signal was picked up from the point of contact of screen and beak,” Skinner wrote. Eventually, they created a version that used three pigeons to make the system more robust—in case one pigeon got distracted at a key moment or something.

American Psychological Association/BF Skinner Foundation

There was, understandably, much skepticism about the feasibility of using pigeons for missile guidance; at one point, Skinner lamented, his team realized “that a pigeon was easier to control than a physicist sitting on a committee.” But Skinner's team persisted, and in 1944 they finally got the chance to demonstrate Project Pigeon to a committee of top scientists and show that the birds' behavior could be controlled. The model pigeon behaved perfectly. “But the spectacle of a live pigeon carrying out its task, however beautiful, simply reminded the committee how utterly fantastic our proposal was.” Apparently, there was much “subdued mirth.”

Although this new homing device was resistant to jamming, could respond to a wide range of gunnery exercises, required no scarce materials, and was so simple to make that production could begin within 30 days, the committee scrapped the project. (By this time, as we now know, the military focus had shifted to the Manhattan Project.) Skinner was left with “an attic full of strangely useless equipment and a few dozen pigeons with a strange interest in a feature of the New Jersey shore.” But vindication came in the early 1950s when the project was briefly revived as Project ORCON at the Naval Research Laboratory, which refined the general idea and led to the development of a Pick-off Display Converter for radar operators. Skinner himself never lost faith in this particular “crazy idea.”